Learning Vietnamese: what's easy, what's hard?

Vietnamese language is much simpler than English language in all aspects: pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. It uses Latin alphabet, therefore, learning it is not very difficult for English speakers. The hardest part is to recognize differences in tones with the tone marks, as it’s a tonal language.

I – PRONUNCIATION

1- It’s a monosyllabic language: every word has only one sound (one syllable).

While there are many two-word terms, each word has only one syllable.

There is a strict rule for pronunciation. One vowel or one vowel combination has only one way of pronunciation, no exception.

Five main vowels:

A: /a:/

E: /e/

I : /i:/

O: /ɔː/

U: /u:/

6 vowels with "Sound Changing Marks":

For the vowel combinations, it’s simply two separate vowels being pronounced linking each other to produce a mixed syllable.

2- Because of strict pronunciation rule, there is a consistency between how the word spells and how the word sounds.

Vietnamese language doesn’t have homonyms, because there is no two different words with the same sound. With one syllable you can only have one way of writing and almost every word has one correct spelling only.

3- The ending consonant is never pronounced.

4- Because all the words are monosyllabic, there is no stressed syllable like English.

5- There is no intonation in a sentence.

Every word is pronounced with the same pitch, same volume. We can say that Vietnamese speech is monotone and flat. You can imagine a line of soldiers with the same height and the same weight.

6- As there is no stress, no intonation, Vietnamese is a syllable-timed language while English is a stress-timed language.

Again, imagine a line of soldiers who are not only with the same height and same weight but also march in the same speed and same movement.

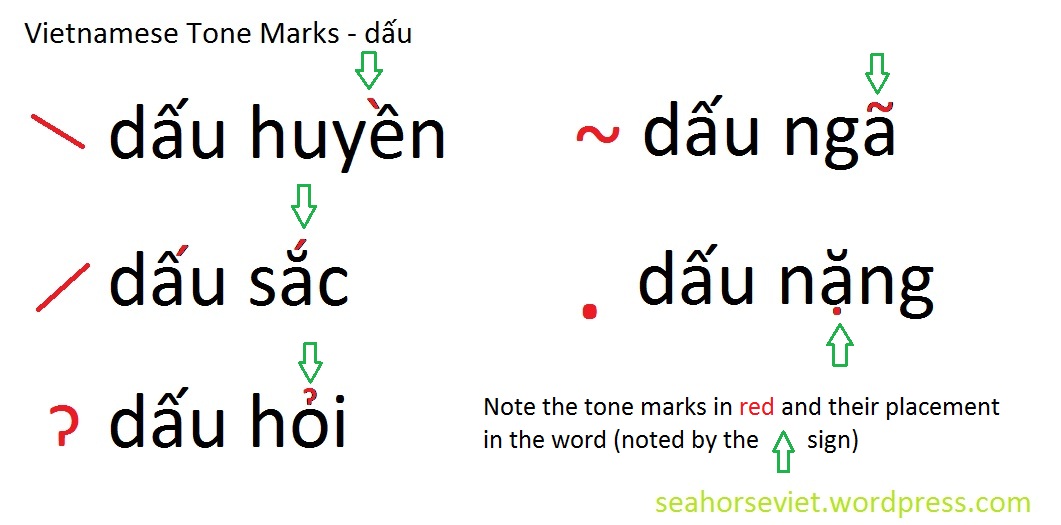

7- However, Vietnamese is a tonal language, because it has 5 main tone marks (dấu):

-The first one (dấu huyền) looks like Reverse Slash Above. With this one, the tone falls.

-The second one (dấu sắc) looks like Slash Above. With this one, the tone rises sharply.

-The third one (dấu hỏi) looks like Hook Above, the tone rises then falls.

-The fourth one (dấu ngã) looks like Lying Hook Above, the tone rises then falls then rises again.

-The fifth one (dấu nặng) looks like Dot Below. The tone falls but very abruptly and heavily.

- Where the word has no tone mark, then the tone is flat.

The tone marks not only change the tone but also give the word a different meaning. The words with the same spelling but different tone marks are not related. They are not the words in a family.

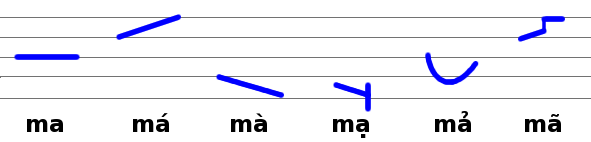

Thus, Ma, Mà, Má, Mả, Mã, Mạ have different tones, different meanings and are not related to each other.

These 5 tone marks apply to 5 base vowels (a, e, i, o, u) to create 25 vowel sounds.

8- There are 3 more vowel-sound changing marks:

• Cone Hat Above : ^ like in Âm. This tone mark is found on top of vowels A, E and O.

: /^/

Ê : like in "eh"

Ô : /ou/

- Smiling Sign Above: like in Ăn. This tone mark is found on top of vowel A only. Ă

• Upperright-Attached Hook : like in Ơm. This tone mark is found at upper right corner of vowels O and U.

Ơ: /3:/

Ư

When applying 5 tone marks to 5 base vowels, it creates 25 vowel sounds and when applying 5 tone marks to 6 special vowels, it creates 30 vowel sounds.

So, in total, Vietnamese spoken language has 66 vowel sounds. It's quite daunting to non-Vietnamese learners.

Recognizing the differences in 8 tone marks and how to mimic the tones are the biggest challenge in speaking Vietnamese for non-native speakers. So far there are no International Phonetic Symbols to express these tone marks, so learners have to listen to native speakers to recognize them. However, the good thing about speaking Vietnamese words with tone marks is even if you say the word with no tone or wrong tone, Vietnamese still can understand you.

It works the same way like foreigners speak English with a heavy accent yet English speakers still understand them.

Examples:

- Instead of saying “Sài Gòn”, you say “Sai Gon”, they know you mean “Sài Gòn”.

- Instead of saying “Tôi” (I), you say “Toi”, they know you mean “Tôi”.

9- Also, there are some Vietnamese sounds that are non-existent in English pronunciation:

- Kh: like Khanh. So Vietnamese would pronounce Khong and Kong differently.

- Ng (at the beginning): like Nguyen. So Vietnamese would pronounce Nguyen and Nuyen differently.

- Nh (at the beginning): like Nha. So Vietnamese would pronounce Nha and Na differently.

Though much smaller than the US, Canada and Australia, the varieties in accent all over the country make Vietnamese listening comprehension a challenge to non native speakers. In general, there are 3 main accents: Northern, Central and Southern. But among them, there are sub-accents. For example, among Northern, Hanoi accent is different from Nam Dinh accent. Among Central, Hue accent is different from Nghe An accent. Among Southern, Saigon (Hochiminh city) accent is different from Mekong Delta accent. Hanoi accent is the standard, as pronunciation of those who were born in the capital is the most accurate to the spelling.

II- GRAMMAR

As a compensation for pronunciation, the grammar of Vietnamese language is very simple. Vietnamese is an isolating/independent language. The nouns or verbs don’t change accordingly with changes in singular-plural mode, in first-second-third subject, in time of action, in modes of verb etc. Instead, Vietnamese language uses indicator-words before the original nouns or verbs for all those changes.

1- Verb tenses: Only one Present tense, only one Past tense and only one Future tense.

Vietnamese are not so sensitive, so conscious about the time when the action happens like English language. So they use Tense Markers before the verb but keep the verb in base form.

- For actions happen in the present, Vietnamese add Present tense marker Đang before the verb or in case there is an adverb of time then no Đang is needed.

For example: Tôi đang học Anh văn (I am learning English).

Tôi học Anh văn mỗi ngày (I learn English everyday)

- For actions happened in the past, Vietnamese add Past tense marker Đã before the verb or in case there is an adverb of time then no Đã is needed.

For example: Tôi đã đi chơi Paris năm rồi ( I visited Paris last year)

Tôi đi chơi Paris năm rồi (I visit Paris last year)

In fact, the second sentence is more popular; because there is adverb of time Năm Rồi (last year) so Vietnamese don’t bother adding Đã before the verb Đi Chơi (visit). Using Đã too often causes the speaker sound unnatural, unnative.

- For actions happen in the future, Vietnamese add Future tense marker Sẽ before the verb or in case there is an adverb of time then no Sẽ is needed.

For example: Tôi sẽ đi chơi Paris năm sau (I will visit Paris next year)

Năm sau tôi đi chơi Paris (Next year I visit Paris)

2- The Verb doesn’t change with the subject.

For example: Tôi học Anh văn – Nó học Anh văn ( I learn English – He learn English)

3- The verb To Be (thì, là) is usually omitted if it follows by an adjective:

For example: Cô ấy đẹp (She beautiful) but Cô ấy là một học sinh (She is a student).

4- Because Vietnamese verbs are not inflected, so there are no auxiliary verbs like English.

- Questions are formed by :

Subject + Có (have) + verb + Object or nothing +Không (no)?.

Ex: Em có yêu anh không? (You have love me no?)

- Answers are formed by some confirmative words like Có (have) - Vâng/Dạ/Ừ/Phải (yes) – Đúng rồi (correct, right) or some negative words like Không (no) Không phải (no) Không đúng (no correct).

- Negative statements are formed by Không + verb. Ex: Em không yêu anh (I no love you).

5- No change from singular noun to plural noun, but plural indicator Những or Các may be added before the noun.

For example: Một cái ghế - Hai cái ghế (One chair-Two chair)

Một cái ghế - Những cái ghế (A chair-Some chair)

6- While Possession in English is formed by Of or ‘S, Vietnamese has Of only (Của).

Ex: Cái nón của ông ấy (the hat of him). It can even be omitted. Ex: Cái nón ông ấy (The hat him). There are no equivalent Possessive Pronouns (his, hers, theirs, ours) in Vietnamese language.

7- Vietnamese Comparative and Superlative of adjectives are simpler than those of English.

There is no difference between long or short adjectives.

- For Comparative, Vietnamese adds Hơn after Adjective. Ex: Đẹp hơn (more beautiful), Xinh hơn (prettier).

- For Superlative, Vietnamese adds Nhất after Adjective. Ex: Đẹp nhất (the most beautiful), Xinh nhất (the prettiest).

8- Normally, the adjective is after the noun.

Ex: Căn nhà màu xanh (The house green).

Except when the two-word noun is a Chinese-Vietnamese term, then the adjective is before the noun. Ex: Siêu thị (supermarket), because Siêu (super) and Thị (market) are both Chinese Vietnamese terms.

However, there are two complex issues in Vietnamese grammar:

9- The way Vietnamese address (call) each other can be very complex to non-native speakers.

While for English speakers, “you” is a catch-all pronoun to the person you are talking to, Vietnamese language has a dozen of you-pronouns, depending on the gender and age of the person the speaker is talking to. In original sense, they are kinship terms, but Vietnamese use them for both relatives and non-relatives. This addressing rule is age-based and gender-based, as Vietnamese culture is Confucius-influenced, which expects one to respect those who are older. But this is also an indication that Vietnamese people are friendly to each other and to tourists, as if they are supposed to treat everybody like relatives.

| MALE | FEMALE | ||

| Older than speaker | Younger than speaker | Older than speaker | Younger than speaker |

| Ông (grandpa) | Bà (grandma) | ||

Bác (older-than-dad uncle) Chú (younger-than- dad uncle) | Bác (older-than-mom aunt) Thím or dì (younger-than-mom aunt) | ||

| Anh (older brother) | Em (younger brother) | Chị (older sister) | Em (younger sister) |

Cậu (original sense: younger-than-mom uncle) Chú em | Cô (original sense: younger-than-dad aunt) Cô em | ||

| Cháu (nephew) | Cháu (niece) | ||

| Mày (rude or inferior you) | Mày (rude or inferior you) | ||

To make it even more complex, if the person they are talking to is at the same age, Vietnamese can also call Ông (male you), Bà (female you), Mày (very friendly you), Bạn, Bồ (friend) or Cậu (buddy).

Ông is also the equivalent of "Mr.", Bà is also the equivalent of "Mrs" and Cô is also the equivalent of "Miss".

To make it easy for foreigners, I would suggest if the person you are talking to seems to be in middle-old age bracket, you call them Ông (male) or Bà (female). If they are young, call them Anh (male) or Chị (female) or if very young, call them Em (both male and female).

The same as no universal You in Vietnamese language, there is no universal I. How Vietnamese call themselves in conversation depends on how they address the talking partner. But for foreigners, I would suggest you say Tôi (I) to every Vietnamese you talk to.

10- The classifiers or “special articles” before Vietnamese nouns are a challenge to Vietnamese language learners.

While English has only 3 articles: A, An and The, Vietnamese language is full of those classifiers. Classifiers are used to give objects an attribute such as shape or animacy and untranslatable into English. So many examples below:

- Con dao (con knife)

- Cái kéo (cái scissors)

- Chiếc chiếu (chiếc mat)

- Sợi chỉ (sợi thread)

- Cọng lông (cọng hair)

- Cuốn phim (cuốn camera film)

- Cây vàng ( cây gold)

- Ngọn cỏ (ngọn grass)

- Đóa hoa (đóa flower)

- Chiếc lá (chiếc leaf)

- Etc.

While Con is usually used for animals like Con Chó (dog) Con Mèo (cat) etc. and Cái is usually used for objects like Cái Ghế (chair), Cái Bàn (table), it’s an exception for Con Dao (con knife) but not Cái Dao (cái knife). Asking them why is the same as asking English speakers why Weight is pronounced /weit/ but Height is pronounced /hait/. So just learn by rote and use them.

III- VOCABULARY

- Vietnamese vocabulary is about 1/25 of English vocabulary, which means less than 40,000 single terms. About 70% them are sophisticated terms (relating to economy, politics, science, technology, literature...) that have Chinese language’s origin, so they are called Chinese-Vietnamese terms (từ Hán Việt).

- 100 years of French domination also left a linguistic legacy: hundreds of Vienamese terms have French origin. Ex: cà phê (cafe).

- The longest Vietnamese word has only 7 characters: Nghiêng, so spelling Vietnamese should be very easy compared to English. Absolutely no spelling competition, regional or national.

- Due to a limited vocabulary, Vietnamese language has to use many original English terms as they have no Vietnamese equivalents.

To sum it up, Vietnamese language is not without challenges to Westerners, but in general, thanks to its use of Roman alphabets and its simplicity in grammar and spelling, it’s fairly easy to learn.

As Vietnam is growing in status as tourism and work destinations, more and more Westerners gain proficiency in Vietnamese language. Some sing and speak and write Vietnamese so well that they surprise native Vietnamese speakers. Examples are:

Dalena: https://www.facebook.com/Dalena-133572258977/

Kyo York: https://www.facebook.com/kyoyorkvn/.

© Tim T. Hoang

Member of TESL Canada

14/6/2016